Latecomers!

We are all Latecomers. We think it’s all over, like the people on the pitch, but so did the Long Ago.

[The Long Ago in action.]

Latecomers!

I mean Latecomers in the sense of latecomers to this Conference or this Substack.

Here’s a recap:

I am a 62-year old poet who will begin a four-year training in psychotherapy in September. I’m currently doing an NHS observership in mental healthcare south of the river and a Foundation course in psychoanalysis north of the river. I’ve been thinking about how and where and why the fields of poetry and psychology connect - or don’t - for quite a while now, publishing speculations and thoughts right here.

Before I knew it, I had organised a conference by mistake.

And have, since January (specifically from 23rd January: Poetry and Psychotherapy: friends, siblings, rivals, or what? - and every post since then) been publishing and considering the excellent contributions of subscribers.

We break for Danish pastries and do all sorts in the evenings.

This is not work towards conclusion or definition. It is a welcoming of insights, experiences and, yes, objections.

Do you know the etymology of the word OBJECT? Object as noun-meaning-thing or object as verb-meaning-protest? Same. ‘Ob’ is against, and ‘ject’ is throw, so it is roughly ‘something thrown into your path against you’. Thus, like a bright child to a busy parent, OBJECTION reminds OBJECT of its roots.

[An Object in Action.]

The structure of the conference is therefore determined by chance: who spoke first and what they spoke of. I’ve been mostly taking the contributions in the order they came, except when something was sharply relevant and called out to me from the floor.

This allows me to proceed rather in the way I teach poetry, by way of Spiralling, or what I call Spiralism. Spiralling has mostly a negative and downward connotation -spiralling into debt or addiction, say - but there’s no reason why it should have. You can spiral upward, and, even if you spiral downward, your movement can be towards light, it depends what substance you’re spiralling through.

It the substance is composed of light and thought, nothing but good can come of it.

What it means in teaching is to raise a subject, move on from it, forget it for now, and then return to it in changed light, perhaps knowing more, perhaps knowing less - by which I mean presuming less.

I discovered it as a by-product of never writing a Teaching Plan. I don’t always know, or simply can’t remember, if I’ve said something before in a class, but something that arrives at a different time is NEVER A REPETITION, because it arrives in a world that’s heard something like it and wouldn’t mind hearing it again. That’s a different world it arrives in. This was the case with my teacher Walcott; a lot of what he said in class then said again later I couldn’t figure out for years, but I knew I wanted to. If you only read from texts you’ll repeat yourself.

All Socrates knew was that he knew nothing.

My version of this is to try to know less every year; or at least, to presume less. I tell the poets in my class that I only know three things but I really really know them. The second ‘really’ is usually ruder than that, but Socrates is listening.

***

As the son of a scientist who loved the arts, I was brought up in awe of folks who live for both.

Though at school I was weak in sciences and dropped them all as soon as I could - only the British drop so many subjects so young, and only the British think it’s a good thing - it seems that what’s emerging in this midlife is an inclination to cross from one field to a second, breathing, I suppose, the air of the one as I approach the other.

***

Laura Webb is a poet studying with me at the Poetry School; she’s also a junior doctor, therefore one who knows about crossing fields. She writes:

‘I think it comes down to functions. You could draw a Venn diagram of "Functions of Psychotherapy" and "Functions of Poetry" and the crossover would be poetry-as-therapy. Elsewhere on the "Psychotherapy" side you'd have CBT (challenges, cognitive biases or exaggerations), family therapy (heals interpersonal relationships), exposure therapy (reduces anxiety from a triggering stimulus) etc. Elsewhere on the "Poetry" side would be poetry-as-storytelling, poetry-as-manifesto, poetry-as-entertainment etc. So there's a crossover.

But not all poetry is therapeutic, and not all therapy is poetic.

I suppose both psychotherapists and poets ask "What function do I need this therapy/poem to serve?" but perhaps poets don't consciously consider this until the later stages of editing. To ask the question when you've only just conceived the idea for a poem can spoil the creative flow, make it feel less authentic, more performative. Whereas for psychotherapists, this question will inform their entire treatment plan from the start.’

***

This is admirably clear-sighted, and helps to remind us that the wrong way to connect these fields would be to take down the fences or silt up the river and make them seem the same thing, or a thing that could easily turn into another. ‘Good fences make good neighbors,’ as Frost said, or said his good neighbour said.

The distinctive word Laura uses is function. This ought to be straightforward in the world of psychotherapy: someone is anxious or depressed and pays an expert to make them feel better. I have not, by the way, had too much of experts. In the writing of poetry it’s more complicated, and Laura is right to point out that the question of function is rarely welcome in the process of composition.

In your average Q and A, the two questions most dreaded by professional poets are these:

‘Where do you get your ideas?’

and

‘Who do you write for?’

I won’t speak for anyone else, but to that second question I’ve always rambled for a couple of minutes until I hear my own noise subside and end up saying ‘probably myself’. This isn’t to say one doesn't care about the reader - I’m looking at you and thinking about you right now, ffs - it’s to say one cares about the craft, about doing the thing as well as it can be done on earth, and the power of that in a working poet fills the space available.

But away from the poet in their white-hot loneliness of writing - let’s not forget the loneliness, in our world of clamouring workshops and convivial retreats - you find the teacher of poetry. Here’s where the convergence interests me most.

Time to spiral.

I’ve been struck rather frequently in my teaching practice by something that might strike you as too simple to say: How happy it makes poets to get better. To grasp form, to go deeper, to throw off old habits, to go from having thirty decent poems to having three and not minding. I know all this because I went right through it.

Now it would be facile to say that making a poem better is equivalent - let alone equal to - making a person better. (Making them feel better, not be better on some abstract moral chart!)

But, taking the cue from the pun in the language -

MAKE IT BETTER -

and you don’t have to be a Freudian to listen out for puns; if you’re wearing long Lacanian trousers you should listen even harder -

it made me think along these lines: If feeling better is an outcome of making poems better, what if you flipped the equation? What if writing better poems was an outcome, and feeling better was the practice?

Would that not be psychotherapy? This is my research field. I don’t mean at a university, I mean in a field.

[A field in action.]

***

Talking of fields, and with apologies to women for the gendered generalities of its time, I hand over to my good neighbour Frost, and ‘The Tuft of Flowers’:

...The butterfly and I had lit upon, Nevertheless, a message from the dawn, That made me hear the wakening birds around, And hear his long scythe whispering to the ground, And feel a spirit kindred to my own; So that henceforth I worked no more alone; But glad with him, I worked as with his aid, And weary, sought at noon with him the shade; And dreaming, as it were, held brotherly speech With one whose thought I had not hoped to reach. ‘Men work together,’ I told him from the heart, ‘Whether they work together or apart.’

***

We take a break, during which, in traditional conference style, I sit down with some folks who didn't ask me to and start banging on about something.

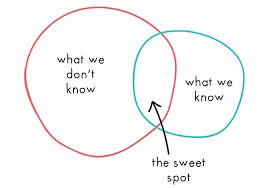

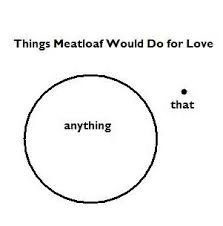

Hey what’s not to like about a Venn diagram? I’ve always been a fan, its clarity, simplicity and beauty-for-all-ages, so I share some old favourites…

Thinking of the 'object' and the spiral maybe more of waves of a tide coming in or even a receding of understanding. As an autistic person, as in, in common with many autistic people , I experience the world as forms and colour and not as objects which I can identify. This requires thought and effort. Bridget Riley, waves of geometry but in fact hand drawn, calls this preconceptual perception. Much to muse on before the naming in poetry and psychology perhaps.

This just gets more fascinating as we delve deeper (or spiral higher?) The virtuous circle you describe (feel better -> write better poems -> feel better etc.) could be set in motion by either poetry or psychotherapy. In which case they are different starting points which converge on the same outcome, i.e. better mental health and satisfaction with life.

The great thing about poetry-as-psychotherapy is that your clients should leave with the skills to maintain their mental health long-term - as long as they keep writing, or come back to it when they have a blip in their life. Which would potentially reduce the number of people who needed to be re-referred for additional courses of therapy further down the line.