Do Not Write Another Poem

Until you’ve listened to this.

This is a bird pecking for seed on a background of gravel.

In the work of the great neuroscientist and philosopher Iain McGilchrist, this image is the crystallisation of why our brains are divided into left and right hemispheres.

The eye you can’t see is looking for seeds. The eye you can see isn’t. Here’s McGilchrist:

'How are you to focus closely on what you are doing when you are trying to pick out that grain of seed from the grit on which it lies, while at the same time keeping the broadest possible, open attention to whatever may be, in order to avoid being eaten? ...What we know is that the division of the hemispheres makes the apparently impossible possible. Birds pay narrowly focussed attention on what they are eating with their right eye (left hemisphere), while keeping their left eye (right hemisphere) open for predators...'

The bird’s right eye (left hemisphere) focuses solely on finding the food, its left eye (right hemisphere) remains aware of the wider picture - am I safe? will this help? is there time?

The left brain apprehends, seeks, finds, literally grasps; the right brain comprehends, sees, understands, metaphorically grasps.

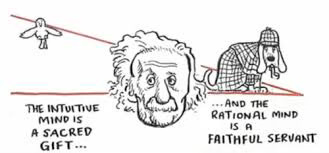

Fast forward a few billennia, and a Dr Einstein is putting it this way:

Or Master and Emissary, as McGilchrist called them in his famous book. As he points out, the bridge between the hemispheres - the corpus callosum - is remarkably narrow, and appears to serve not so much to connect the halves of the brain, but to keep them distinct, working at their different and essential tasks.

What’s this got to do with poetry? Well. A lot of my teaching and writing on poetry stems from my contention that most of it isn’t good and won’t be remembered. Those two outcomes, quality and memorability, are wedded in my mind, which may not apply to other minds.

These instincts began long ago as preference, evolved into taste, then began to develop aesthetic and philosophical grounds. Ground to peck for seed in, anyway.

Pecking for seed among the gravel is itself a strong metaphor for staring at a white space trying to write well. What if left-brain poems were serving functions such as these - and I can list them because I’ve felt them all in my time and I’m sure you can find some of yours in there too…

I get better at this. I impress people around me. I surprise myself. I point out things are like other things. I sound like my heroes. I show my parents it was worth it all along. I get applause. I get employed. I become more attractive. I seem interesting and deep. I am borne in mind.

That’s the pecking for seed.

So what’s the right brain doing, what’s the left eye watching for?

Think of the bird above: am I safe? will this help? is there time?

Or take an intermediate point: early humankind, always a way of understanding why we do what we do. What would the first artists be expressing: this is our story, remember our story, make friends of these, beware of those, eat this, not that, go there, not there…

In poetry of any time or place, including T S Eliot’s ‘now and England’, this would suggest clarity and memorability along with truth and beauty:

Am I safe? are my kind safe? will this help us? is there time? what’s our story? what went wrong and is it going wrong again? can I make the passing days better, kinder, or sweeter, either way more comprehendible? Can these words be handed down through generations of us?

None of the left-brain impulses are any damn good here.

So, as the T S Eliot Prize galleon sails by again with its thoroughly mixed and settled-in-transit cargo, I ask:

Is this a good poem by its own lights? well done you.

By the lights of the world? I mean - in the light of the world.

I mean - has this poem been written in light of the world?

***

You can write another poem now.